Background: First episode of Psychosis in a young individual, if untreated for long time, leads to long term poor outcomes. Poor mental health literacy in non Psychiatric health professionals is one of the main barriers to help seeking & treatment in low and middle income countries. There is lack of qualitative studies exploring health professionals’ response to patients presenting with Psychosis. Hence we decided to evaluate the experiences of caregivers of persons with first episode of psychosis when they presented to other health professionals in a qualitative way. Aim: The aim of the study was to evaluate caregivers’ experiences in help seeking with other health professionals, with a qualitative approach in patients with first episode psychosis. Material & Methods: Qualitative interviews were conducted with sixty one caregivers of people with first episode Psychosis in relation to other health professionals’ response to their help seeking. Statistics: Thematic analysis of interview transcripts was conducted. Results: Sixty one caregivers were interviewed for the study after excluding eleven caregivers for different reasons. Half of respondents (n = 32) themselves contacted health professionals who did not then initially recognize psychosis. The reactions of health professionals were as follows –asking the patient to relax, describing this as a part of generalized weakness, prescribing sleeping pills (most of the time alprazolam), multivitamin tablets. There were exceptions in 3 of the patients who were referred to psychiatrists after convincing the family member about mental illness. Discussion: The vague nature of many early psychotic experiences creates difficulties, especially for those without specialist training, in distinguishing illness. Stigma, significant unawareness of treatment methods and biological causes of psychiatric disorders in medical professionals appear important hurdles in reducing DUP. The medical students in their clinical studies in final year need to study mandatorily about depression and psychosis and about instituting the primary levels of treatment.

First episode of Psychosis in a young individual, if untreated for long time, leads to long term poor outcomes. India is a country with limited resources in handling mental illnesses. Several studies reveal poor knowledge about mental illness in the general population and stigmatizing attitudes towards people with mental illness. Health Professionals are no exception to this rule. A study done in rural Nepal to assess mental health gap in Primary care providers reported limited training, lack of knowledge and skills, and discomfort in delivering mental health care ( Hirachan et al., 2016). Mental health literacy (MHL) has been defined as “knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders which aid their recognition, management or prevention.”(Jorm et al., 1997). According to this definition, MHL includes: the ability to identify specific disorders; being aware of how to search information; knowledge of related risk factors, causes, self-management, and how to seek available professional help; and having attitudes that promote identification (Jorm et al., 1997). While much research has been done in Western countries on the MHL of both the public and professionals (O’Reilly, Bell & Chen 2010; Reavley & Jorm 2011; Morgan, Reavley & Jorm 2014), no published data are currently available on the MHL of non-mental health professionals in other middle and low income countries.

In India, Psychiatry is not integrated into primary health care and psychiatry continues to be ignored as a subject in undergraduate courses. The implementation of public education campaigns and training of non- psychiatric health professionals on mental health and clinical depression has been neglected in several countries, including India.

A cross-sectional survey conducted over a 4-week period in Gujarat, India among resident physicians and community health workers about their knowledge and views on clinical depression revealed considerable stigma and misinformation about depression especially among health care workers in India (Almanzar et al., 2014). There is lack of qualitative studies exploring health professionals’ response to patients presenting with Psychosis. Hence we decided to evaluate the experiences of caregivers of persons with first episode of psychosis when they presented to other health professionals in a qualitative way.

Aim

The aim of the study was to evaluate caregivers’ experiences in help seeking with other health professionals, with a qualitative approach in patients with first episode psychosis.

MATERIAL & METHODS

The research took place from May 2016 to March 2017 in a Psychiatric hospital located at a district headquarters in South India. This study was a part of a bigger study published elsewhere (Kalmane, Pavitra & Sridhara, 2019). Our sample consisted of all newly registered patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria. Participants were recruited through clinical services. Inclusion criteria were subjects of both genders, above the age of 18 years, fulfilling ICD -10 diagnostic criteria for any type of psychotic disorder, consultation with the psychiatrist for the first time, not on any psychotropic drugs with the exception of use of short duration benzodiazepines, giving written informed consent, and willing to spend required time for the interview. Participants were required to understand and speak the local language, i.e., Kannada. The study design was approved by the institutional ethics committee. The interviews were conducted without a time bound framework and on an average, an interview lasted for 2 hours. The interviews were conducted by authors 1 and 2 both having a postgraduate degree in Psychiatry and working in this area since 5 and 12 years respectively. The participants narrated their experiences in response to a priming statement, which was fairly open-ended and covered most aspects of disclosure.

Topic guide for semi-structured interviews covered was obtained from an earlier study (Sanna & Nicola, 2011) with permission and with suitable modifications for the cultural setting. Additional probes were used to elicit more information as appropriate. All interviews were tape recorded.

Statistical Analysis

A thematic analytic approach within an interpretative-phenomenological framework was used. Content analysis was used here as a research technique for the objective, systematic and quantitative description of the manifest content of communication. In other words, it breaks usual communication in to more elementary semantic and syntactic structures and calculates frequencies of occurrence. The sample for this analysis may be an audio taped communication which is transcribed and later broken in to clauses for analysis or written narratives. The unit of analysis is often a clause, sentence or paragraph but there are no clear cut guidelines to determine the choice of unit. The categories used for analysis may be predetermined based on the theoretical concern or the data may be allowed to generate their own categories by statistical measures. In the present study the paragraph was the unit of analysis which was further broken up into themes.

We used both deductive and inductive approaches, seeking answers to our initial research questions while also exploring themes that emerged directly from the data. The software used for the analysis was atlas ti version 7.0.83.The responses of the patients for each of the questions were coded using the “codes” option. Families (groups) were created using socio-demographic variables such as gender, marital status, occupation, family size etc. Cross tabulation was done with the codes against each of the variables.

RESULTS

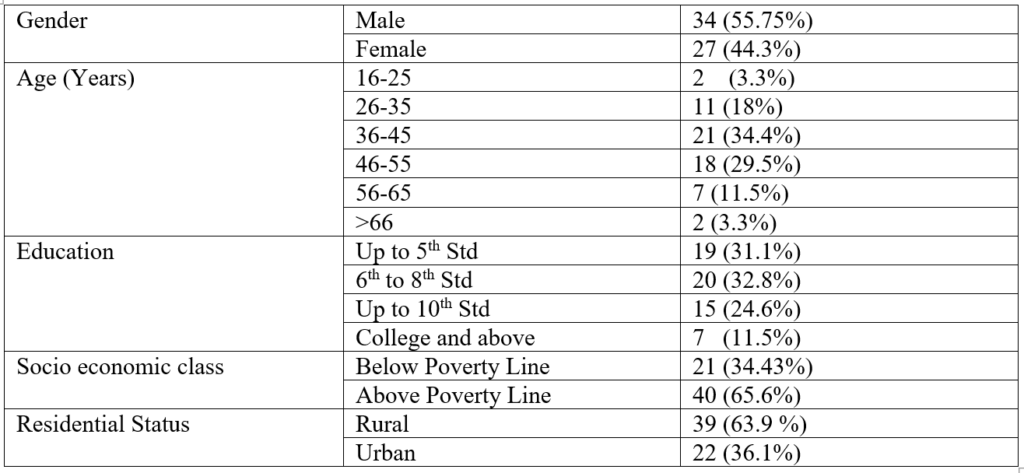

Seventy two caregivers met the inclusion criteria. However 4 of them failed to give informed consent and 7 of them did not have reliable information. Hence sixty one caregivers were interviewed for the study of which 34 were males and 27 were females. Family history of mental illness was present in 16(24%) of the subjects. The caregivers’ socio demographic profile is given in table 1. Duration of untreated psychosis ranged from shortest period of 5 days to longest duration of 8 years (DUP Median- 18months).

Table 1:-Caregiver Characteristics

The diagnoses of psychotic disorders included: Acute Psychosis (n=13), Schizophrenia (n=17) Psychosis NOS (n=28), Persistent delusional disorder (n=3).

Results are organized thematically, describing caregivers’ responses to the priming statements related to Health professionals response to help seeking.

Although for most respondents, help-seeking was initiated by a relative/friend /family member, half of respondents (n = 32) themselves contacted health professionals who did not then initially recognize psychosis. Some respondents were reluctant to divulge problems and correspondingly vague when describing symptoms, often emphasizing physical problems over mental health difficulties. Further this was evident by the available prescription of earlier consultation. The reactions of health professionals were as follows –asking the patient to relax, describing this as a part of generalized weakness, prescribing sleeping pills (most of the time alprazolam), multivitamin tablets. There were exceptions in 3 of the patients who were referred to psychiatrists after convincing the family member about mental illness. Even in professionals who recognized this to be a mental illness they thought it was depression and told carers that patient has ‘some depression’.

Half of the sample (n=32) had not seen a doctor where as the other half had consulted either a homeopathic/ayurvedic practitioner, or a primary health care consultant. Two were seen by neurologist-neurosurgeon. Out of these 29 patients, 22 came to a psychiatrist on their own or guided by a relative which was after the symptoms increased even after treatment with Alprazolam and multivitamins. The other 7 patients were referred by the health professionals after the symptoms did not come down with treatment.

“Homeopathic doctor gave tablets for headache and sleep; He said he will be alright, not to worry. He also told us to follow some dietary advice. We also saw an Ophthalmologist for headache. Initially he gave spectacles, later when problem persisted he suggested us to go to a psychiatrist. He said he requires some counseling.” ———– Brother of a 39 year old male patient with Psychosis nos.

Our family doctor told us that during the stopping of menstruation these things routinely happen. He gave her tablets for sleep. In the next 2 days, problems worsened. We went back. He asked us to go to a psychiatrist. But we didn’t agree. In fact, patient was angry. She said that she isn’t mad. We were also unsuccessful in convincing her.” ———- Sister of a 48 year old lady with Paranoid Schizophrenia.

“A neurosurgeon treated him. Hence we thought this was a nervous weakness. He treated him for a year. We were fed up of medicines. But my husband was not better, he remained same. I thought getting some counseling will make him better and we also then can stop medicines. So we stopped seeing neurosurgeon and consulted a psychiatrist.” ————- Wife of a 42 year old male patient with Psychosis nos.

DISCUSSION

The vague nature of many early psychotic experiences creates difficulties, especially for those without specialist training, in distinguishing illness symptoms from other medical problems or depression as a noted by earlier studies too (Phang et al., 2010). Medical professionals other than psychiatrists have been identified as major step in the pathways to care (Chadda, Agarwal, Singh & Raheja, 2001). These medical professionals were presented with vague, or physical rather than mental symptoms, illustrating why it is difficult for them to identify early psychosis. Also high levels of stigma for a diagnosis of psychosis, easy acceptance of depression as a diagnosis by family members who believed counseling would suffice for depression where as psychosis may have warranted lifelong treatment prompted medical professionals to give a diagnosis of depression even when the symptoms were well recognized. Majority of the patients treated by these practitioners (whether Allopathic, Unani or Ayurvedic) had a prescription of multivitamins and Alprazolam for sleep. Participants in this study typically reported significant delays in pathways to care once help-seeking had been initiated.

Stigma, significant unawareness of treatment methods and biological causes of psychiatric disorders in medical professionals appear important hurdles in reducing DUP. The medical students in their clinical studies in final year need to study mandatorily about depression and psychosis and about instituting the primary levels of treatment.

Implication

Mental disorders are common and their disorders are not often detected when seen in primary care setting (Üstün & Sartorius 1995). It is also noteworthy that psychological morbidity is a common feature of physical disease and it is important to recognize emotional distress by a primary health care professional. According to World Health Organisation, training primary care and general health care staff in the detection and treatment of common mental and behavioural disorders is an important public health measure. In this regard, NIMHANS ECHO has been involved in running various tele-ECHO sessions/clinics, Blended with Digital Course Certificate program for the learners like Physicians, Primary Care Doctors, Residents, Counselors, Community Health workers etc to exponentially increase the Skilled Manpower in our country. (http://vlc.nimhans.ac.in/?page_id=3008). If this can be implemented by the government of India as a part of national program and Psychiatry training made compulsory in Medical Undergraduate courses, help seeking for patients with mental illness becomes easier, thereby reducing the duration of untreated illness and improving outcomes.

REFERENCE

- Acharya B, Hirachan S, Mandel JS, van Dyke C(2016). The Mental Health Education Gap among Primary Care Providers in Rural Nepal. Academic Psychiatry40,667–671.doi: 10.1007/s40596-016-0572-5.

- Almanzar S, Shah N, Vithalani S, Shah S, Squires J, Appasani R, Katz CL(2014) Knowledge of and attitudes toward clinical depression among health providers in Gujarat, India. Ann Glob Health; 80(2):89-95. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2014.04.001.

- Chadda RK, Agarwal V, Singh MC, Raheja D(2001) Help seeking behaviour of psychiatric patients before seeking care at a mental hospital. Int J Soc Psychiatry; 47(4):71-8.

- Digital Courses, Nimhans DigitalAcademy Virtual KnwledgeNetwork(VKN);Centre for Addiction Medicinehttp://vlc.nimhans.ac.in/?page_id=3008.

- Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Christensen H, Rodgers B, Pollitt P(1997)”Mental health literacy”: a survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med J Aust;1997; 166: 182–86.pmid:9066546

- Kalmane. S, Pavitra. K.S, Sridhara. K.R (2019). Breaking the Barriers: A Qualitative Study of Caregivers’ Experience of First Episode Psychosis in a Town in South India. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 7(1), 471-481. DIP:18.01.053/20190701, DOI:10.25215/0701.053

- Morgan AJ, Reavley NJ, Jorm AF (2014) Beliefs about mental disorder treatment and prognosis: comparison of health professionals with the Australian public: Aust N Z J Psychiatry; 48: 442–451. pmid:24270309.

- O’Reilly CL, Bell JS, Chen TF (2010) Pharmacists’ beliefs about treatments and outcomes of mental disorders: a mental health literacy survey. Aust N Z J Psychiatry: 2010; 44: 1089–1096. pmid:21070104.

- Phang, Cheng-Kar & Midin, Marhani & Abdul Aziz, Salina. (2010) Prevalence and Experience of Contact with Traditional Healers Among Patients with First-Episode Psychosis in Hospital Kuala Lumpur. Malaysian Journal of Psychiatry;19

- Reavley NJ, Jorm AF(2011) Recognition of mental disorders and beliefs about treatment and outcome: findings from an Australian National Survey of Mental Health Literacy and Stigma: Aust N Z J Psychiatry: 4; 890–898. pmid:21942746.

- Sanna T, Nicola M. Service user and career (2011) experiences of seeking help for a first episode of psychosis: a UK qualitative study.BMC Psychiatry: 2011; 11: 157.