The current research examines the anticipated long-term impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Indians’ lifestyle and thinking, using interviews and a self-constructed ‘Anticipated Changes Post Pandemic’ Scale. The sample comprised of 1009 Indians (women=637; men=372), across 21 states/Union Territories, ranging between 17-83 years. Analyses included means, standard deviation and percentages. Results showed that COVID-19 seems to have marked psychological implications moving forward. Three types of changes can be anticipated: lifestyle changes (not wasting food, spending less, reducing junk food consumption, becoming more hygienic); changes in mindset towards greater environmental awareness and gratitude towards the mundane; and increased national pride (for e.g., wanting to buy more products made in India) and even boycotting Chinese products. 96.5% agreed that they will not waste food; 72.2% said that they spend less. 92.9% of the sample said that they will become more environmentally conscious after the Pandemic. 55.9% of the sample expressed that they will buy more products made in India; while 41.6% said that they will boycott Chinese products. Implications are discussed.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), a pandemic declared by WHO, has resulted in more than 2,921,438 cases and 203,289 deaths across 210 countries/territories, as of April 25th (World Health Organization 2020). India, despite being in nationwide lockdown since 23 March 2020 has 26,496 confirmed cases 844 deaths. No one alive has witnessed anything even remotely similar to this in their lifetimes, and everybody is at a loss to deal with this pandemic. While the Government and health institutions are taking measures to contain the virus on a war footing, worldwide attention has been focused on control, development of vaccine and effective treatment, the psychosocial aspect of COVID-19 has not received due attention yet.

It must be remembered that a pandemic is also a psychological phenomenon. Hence, psychology is extremely relevant in understanding how people cope or react to such an unprecedented event. Irrespective of differences in each individual’s routines, each one of us has faced disruptions and has found himself coping with unfamiliar living situations. We slept in one world and woke up in another. Our known stressors and anxieties- work, bad boss, toxic relationship, kids, financial worries, body image- suddenly seemed trivial in the face of this monster Pandemic.

Without a doubt, COVID-19 has posed an enormous challenge to psychological resilience. It is perhaps the biggest challenge human beings have faced before. Research data are needed to develop evidence-driven strategies to reduce adverse psychological impacts and focus on the long-term consequences on people’s psyche and behaviour.

Previous research has revealed huge psychosocial impacts on people at the individual, community, and international levels during outbreaks of infection. For instance, Sheikh et al. (2014) found that nearly 39% of surviving respondents of Ebola from the 2014-16 outbreak faced difficulty concentrating on tasks, 33% experienced problems with sleep due to worry, 5%–10% of respondents reported feelings of worthlessness, inability to make decisions, or losing confidence in self. Van Bortel et. al (2016) similarly reported that those affected by Ebola were likely to experience psychological effects due to the traumatic course of the infection, fear of death and experience of witnessing others dying. Survivors also experienced feelings of shame or guilt (e.g. from transmitting infection to others) and stigmatization or blame from their communities. In a study done 6 weeks after the national outbreak of SARS in Singapore, Sim (2010) found significant rates of SARS-related psychiatric (22.9%) and posttraumatic morbidities (25.8%) on the non-infected community. The presence of psychiatric morbidity was also found to be associated with the presence of high level of posttraumatic symptoms. A recent study by Wang et al. (2020) found that even during the initial stage of COVID-19 in China, more than half of the respondents rated the psychological impact of the outbreak as moderate or severe; 16.5% reported moderate to severe depressive symptoms; 28.8% reported moderate to severe anxiety symptoms; and 8.1% reported moderate to severe stress levels.

While there are some researches such as the ones described above that discuss the psychological impact of infectious diseases, research is scant with regard to the changes that occur in people’s mindsets and behaviours, when things go back to normal. The present study tries to get a glimpse into what the future post the pandemic might look like, in terms of changes in people’s mental make-up, personal habits and collective consciousness. The objective of the study therefore is to study the anticipated long-term consequences of COVID-19 pandemic on people’s lifestyle and thinking.

METHODOLOGY

Sample

The target population was the general Indian population. Inclusion criteria were (i) Indians currently residing in India, (ii) aged 18 years or older, and (iii) ability to understand English. The sample for the first qualitative phase of the study comprised of 15 participants from different age brackets: 5 in the 20-21age bracket, 5 from the middle age bracket (30-50 years) and 5 participants from the above 60 years age group.

The sample for the next quantitative phase comprised of 1009 participants (women=637; men=372), covering 21 States/Union Territories including Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Punjab, Rajasthan, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Maharashtra, West Bengal, Odisha, Assam, Meghalaya, Arunachal Pradesh, Ladakh, and Jammu & Kashmir. 73.4% responses came from North India, 11.9% from the West, 9.5% from the South and 5.2% from the East. The sample comprised of 637 women and 372 men. Their age ranged from 18-83 years, mean age being 38.02 years. Nearly 50% of the sample was working, employed in various fields like education, finance, health services, law, real estate, business, etc, 30.22% of the sample was students, 12.5% homemakers, and 7.1% retired. The sample comprised of middle/upper class income strata.

Instruments

The study used both a qualitative and quantitative approach. Thus, two measures were used:

- Semi-structured interview: In the first phase of the study, a semi-structured interview schedule was created to understand the possible lifestyle and mindset changes that will occur after the pandemic is over.

- Anticipated Changes Post Pandemic: Based on the thematic analyses of the interviews, We developed a new scale called ‘Anticipated Changes Post Pandemic’ (See Appendix). Thematic analyses of the interviews revealed broad themes, such as changes in personal habits, spending patterns, mindset change, sentiment of national pride, changes in lifestyle (e.g., traveling, becoming more conscious of one’s health), etc.

Items were written based on these themes identified. A total of 24 items were written based on this. Next, an expert panel comprising of a clinical psychologist, social psychologist, and a general physician was asked to evaluate these items. On the basis of their suggestions, four items were deleted. The next step in scale development was to pilot test it. These 20 items were now given to five respondents: two undergraduate students of psychology, a businessman, a homemaker and a retired Army officer. A discussion with them helped to ensure face validity of this first version. Based on their feedback and agreement among the participants with regard to items that were felt to be weak or erroneous (those with double meanings, uncertain, or inadequate), some items were reworded and some were deleted. After the pilot study, 15 items were selected for the scale administration. A Likert scale ranging from 1 (disagree strongly), 2 (disagree), 3 (neither agree nor disagree), 4 (agree), and 5 (agree strongly) was used to assess the extent of the changes that the participant thinks might occur in his/her lifestyle as a result of this pandemic. In addition, demographic information was sought regarding the respondent’s age, gender, relationship status, family income, occupational status, nature of work, and city where currently residing during lockdown.

Procedure

The research associates conducted 15 detailed telephonic interviews with participants from different age brackets in the first phase of the study. In the second phase, a Google form was created for online administration. Participants were contacted via e-mail, WhatsApp and a post on Facebook. Care was taken to accommodate responses from all parts of India. Participants were told that the purpose of the study was to understand the changes that they anticipate in their lives post the COVID-19 pandemic. Participation was voluntary, and no monetary compensation was given. Participants were informed of their rights, confidentiality was assured. Informed consent was taken electronically before data was collected from the participants.

RESULTS

The analysis included means and standard deviations for all the items and calculation of percentages for the respondents who agreed-strongly agreed, to identify the trends in life after the pandemic.

Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations of all the items of the Anticipated Changes Post Pandemic Scale.

As seen from Table 1, the item that received the highest mean was ‘I will not waste food’, followed by ‘I will become more mindful of my health’, ‘I will become more environmentally conscious’, ‘I will become more hygienic (e.g. washing hands, bathing)’

On the other hand, the items that received the lowest means were ‘I will spend more; there is no point of saving’, I will reevaluate my/my children’s plans of studying abroad and ‘I will cut back on international travel’. This implies that respondents did not agree with these latter changes.

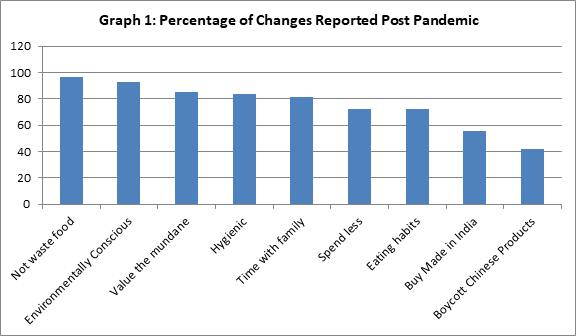

As seen from Graph 1, an overwhelming 96.5% agreed that they will not waste food; 92.9% of the sample said that they will become more environmentally conscious; 85.3% people said that they will now value routine activities like going out with friends, walks, etc. more; 83.6% of the sample said that they will become more hygienic; 81.8% agreed that they will spend more time with their families; 72.2% said that they will reduce expenditure; 72% stated that there would be definite changes in their eating habits in terms of reduced intake of unhealthy/junk food; 55.9% of the sample expressed that they will buy more products made in India; while 41.6% said that they will boycott Chinese products.

DISCUSSION

It seems clear that the experience of the COVID-19 and the lockdown will be life changing. People will see the world differently than they did before, a world that will mark huge changes in people’s mindset and behaviour moving forward. Based on the responses, the anticipated changes have been classified into three:

Changes in lifestyle

We will see significant lifestyle changes in the times to come. For instance, an overwhelming 96.5% agreed that they will not waste food. In a country like India which grapples with scarcity of food, this could be God send. Telephonic interviews showed that people experienced guilt about sitting comfortably in their own homes, putting Instagram pictures and Facebook statuses of culinary delights made by them, when a large section of daily wage earners were without food. It seems that the pandemic has resulted in the middle-upper middle class realizing their own privilege, causing dissonance about their own consumption.

72.2% said that they will reduce expenditure on luxury items like clothes and other accessories, as opposed to a mere 7.5% people who reported that they will spend more as there was no point in saving.91.1% of the participants said that they will take better care of their health. 72% stated that there would be definite changes in their eating habits in terms of reduced intake of unhealthy/junk food. With high importance to cleanliness seen through this pandemic, 83.6% of the sample agreed to incorporate the hygiene aspect (e.g. washing hands, bathing) in their day to day lives.

This is in line with previous research which found that a number of such personal hygiene behaviours became lasting, habitual behaviors after infectious epidemics like SARS. Furthermore, health awareness and positive health-related behaviours may spill over to other areas of health-seeking behaviors. For instance, Lau, Yang, Tsui, & Kim (2006), reported that a very large percentage of the population increased adoption of healthier lifestyle, spend more resources on health, adopted good personal hygiene, used mask when ill with influenza, and avoided risk behaviours in June 2003, as compared with the pre-SARS period. About 60% to 75% of the respondents in their survey reported that they more frequently kept their home hygienic, maintained good personal hygiene, or frequently/very frequently washed their hands. Similarly, Fung and Cairncross (2007) also found that self-reported hand-washing compliance increased in the first phase of the SARS outbreak and maintained a high level 22 months after the outbreak. The decline of hand-washing in Hong Kong after SARS was relatively slow.

Mindset changes

The results point towards two definite trends- one towards greater environmental awareness and two, towards gratitude and mindfulness. 92.9% of the sample said that they will become more environmentally conscious after the pandemic. It looks like what Greta Thunberg could not do, COVID-19 has. Fears of apocalypse from global warming and climate change have become more real and urgent now. The importance of family seems to have increased during times of quarantine. Despite only 6.5% of the sample living alone at the time of data collection, 81.8% agreed that they will continue to invest in more family time even in the future. Further, 67.5% of the sample also said that they will take work more seriously now. After the pandemic which led to severe disruptions in one’s schedules, people seem to be valuing their set routines. 85.3% people said that they will now value routine activities like going out with friends for a simple meal, walk to the park, etc. more. It looks like this pandemic has resulted in people appreciating what they have.

These findings resonate with the concept of post-traumatic growth, where survivors report increased appreciation of life, enhanced closeness and caring in interpersonal relationships, and better cohesion within the affected community (Calhoun& Tedeschi, 2014; Shah & Kuriansky, 2016). Research (for instance, Lies, Mellor, & Hong, 2014) has also underlined the potential role of gratitude as a protective factor against posttraumatic stress (PTS) symptomatology and global distress (GD) in the wake of the 2009 Padang earthquake in Indonesia.

Increase in collectivism

Another sentiment, though less strong, is anti-Chinese and increase in national pride. 55.9% of the sample expressed that they will buy more products made in India; while 41.6% said that they will boycott Chinese products. While China faces long-term damage to its image with long-lasting geopolitical effects, the proactive and rather aggressive approach of the Indian Government towards managing COVID-19 has found many takers. While the first case of COVID-19 in India was reported on 30 January, screening entry into India started from mid-January itself. Increased restrictions on travel followed. A complete nation-wide lockdown was announced on 22 March, when only 236 cases were confirmed, extended to 3 May. It is my contention that countries like the United States, Italy and Sweden contemplated lockdown for a long time, owing in part to their low power distance and high indulgence. Indians, on the other hand, are characterized by high power distance, high restraint, and low uncertainty avoidance (Hofstede Insights, 2020). This led to our willingness to allow ambiguity, accept authority and adhere to strict social norms with respect to social distancing, at least by this section of the population. 60.85% of the sample felt that the efforts of the Government have been adequate. One respondent remarked, “when I see a good leader…acche actions le rahe hai…responsibility sambhal rahe hai…hope aata hai…we are all in this together” (when I see a good leader…he is taking good actions…he is meeting responsibilities carefully…instills hope…we are in this together.”).

The Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi exhorted the citizens to participate in novel tasks such as Janta curfew on 21 March (stay home voluntarily for 14 hours before the forced lockdown) and asked them to come to their balconies and clap and cheer for corona warriors like health providers, police, etc at 5 pm for 5 minutes. On April 5, he asked citizens to switch off electric lights at 9 pm for 9 minutes, and light candles, diyas or mobile lights standing at their doorsteps or balconies to “progress towards light and hope” (PM Modi in an address to the nation). While some attribute this to astrological reasons, such unique measures served the psychological objective of unifying India, and at the same time unified citizens across India.

This pattern is consistent with the pathogen-prevalence hypothesis (Fincher, Thornhill, Murray, & Schaller, 2008), which suggests that collectivism is a response mechanism for coping with disease vulnerability. Similar findings were noted by Kim, Sherman, and Updegraff (2016) after the Ebola epidemic. They found that higher collectivism was associated with a greater perceived vulnerability to Ebola. They suggested that a collectivistic context in which other people engage in group-protective behaviours can provide something akin to psychological herd protection.

Limitations of the present study and Implications

The sample constitutes the middle/upper class strata of the society; no claims are made about generalizability of the same to other income groups. The tool used was not standardized, as no such tool with reported psychometric properties was available. An attempt is made to only predict the changes that might occur in people’s lives after the pandemic, as reported by them. It may be influenced by social desirability bias. Moreover, the classic attitude-behaviour inconsistency (LaPiere, 1934) shows that there is no guarantee that these changes will indeed happen.

The results have significant implications for researchers, policy makers and professionals working in varied areas such as health, consumer research, environmental bodies, etc. Future researches could focus on post traumatic growth and exploring relationships between resilience in the face of pandemics and personal characteristics.

Conclusion

A crisis has the potential to bring out the best in humanity. It seems to have reminded us how important it is to take care of ourselves, our communities, and our mother Earth. One can only hope that the lessons learnt from this pandemic are not forgotten quickly. History has taught us that we are not very good at learning the lessons of the past. Only time will tell if we actually embrace these changes or fall prey to the human propensity of moving on to what is most immediate in our lives.

REFERENCES

- Calhoun, L.G. & Tedeschi, R.G. (2014). Handbook of Posttraumatic Growth: Research and Practice. New York: Routledge.

- Fincher, C. L., Thornhill, R., Murray, D. R., & Schaller, M. (2008). Pathogen prevalence predicts human cross-cultural variability in individualism/collectivism. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 275, 1279–1285.

- Fung, I.C., & Cairncross, S. (2007). How often do you wash your hands? A review of studies of hand-washing practices in the community during and after the SARS outbreak in 2003. International Journal of Environmental Research, 17(3), 161-83. DOI: 10.1080/09603120701254276

- Hofstede Insights (2020). Compare Countries. Retrieved on 17 April, 2020 from https://www.hofstede-insights.com/product/compare-countries/

- Kim, H. S., Sherman, D. K., & Updegraff, J. A. (2016). Fear of Ebola: The influence of collectivism on xenophobic threat responses. Psychological Science, 27(7), 935-944. doi: 10.1177/0956797616642596

- LaPiere, R. T. (1934). Attitudes vs. Actions. Social Forces. 13 (2): 230-237. doi:10.2307/2570339

- Lau, J.T., Yang, X., Tsui, H.Y., & Kim, J.H. (2005). Impacts of SARS on health-seeking bajaviours in general population in Hong Kong. Preventive Medicine, 41(2), 454-462. DOI: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.11.023

- Lies, L., Mellor, D., & Hong, R.Y. (2014) Gratitude and personal functioning among earthquake survivors in Indonesia. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9(4), 295-305. DOI: 10.1080/17439760.2014.902492

- Shah, N., & Kuriansky J. (2016). The impact and trauma for healthcare workers facing the Ebola epidemic. In J. Kuriansky (ed.). The Psychosocial Aspects of a Deadly Epidemic: What Ebola Has Taught Us About Holistic Healing (pp. 91-109). ABC-CLIO, LLC: Santa Barbara, California.

- Sheikh, MA., Gidado, S., Poggensee, G., Nguku, P., Olayinka, A., et al. (2015). An evaluation of psychological distress and social support of survivors and contacts of Ebola virus disease infection and their relatives in Lagos, Nigeria: A cross sectional study−2014. BMC Public Health, 15 (1), 824. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2167-6

- Sim K. (2010). Psychosocial and coping responses within the community health care setting towards a national outbreak of an infectious disease. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 68, 195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.04.004.

- Van Bortel, T. (2016). Psychosocial effects of an Ebola outbreak at individual, community and international levels. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 94, 210–214. doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.158543.

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. (2020). Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health. 17(5), 1729. Published 2020 March 6. doi:10.3390/ijerph17051729

APPENDIX

Anticipated Changes Post Pandemic Scale

- I will not waste food.

- I will spend less on clothes, accessories, etc.

- I will become more mindful of my health.

- I will spend more time with family.

- I will take my work more seriously.

- I will change my eating habits in a positive manner (reduce junk food intake, etc.)

- I will spend more; there is no point of saving.

- I will become more hygienic (e.g. washing hands, bathing).

- I will buy more things that are made in India.

- I will boycott Chinese products.

- I will become more environmentally conscious.

- I will cut back on international travel.

- I will reevaluate my/my children’s plans of studying abroad.

- I will go more with-the-flow rather than plan rigorously for the future.

- I will value routine activities (like going out with friends, walks, etc.) more.